Dolores Hayden’s essay, “What would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work,” from the Spring 1980 Supplement of Signs magazine, examines how architectural design and urban planning in the United States have been instrumental in constraining women’s equal participation in physical, social, and economic life and explores alternative egalitarian housing solutions that support women. Hayden argues that the adage, “a woman’s place is in the home,” has been the de facto principle governing residential design in the “urban region,” which encapsulates cities, suburbs, and exurbs. She reflects on how the design, siting, and financing structures of residential architecture are orchestrated around the “ideal nuclear family,” which views men as breadwinners, engaged in the workforce and public life of the city, and women as the symbol of domestic order, confined to the private life of the home and the needs of the family. Such planning choices, she writes, have created hardships for women who break out of their traditional roles as homemakers and enter the workforce. She rejects the home as an homage to “patriarchal fantasies” and male authority and proposes measures to address this shortfall through the work of community organizing, warning against market solutions that she deems exploitative. The Non-Sexist City that Hayden proposes unites housing, services, and jobs to support employed women and their families by adapting a financial model like those of limited-equity housing cooperatives.

According to Hayden, the rise of the suburb and homeownership in the early twentieth century altered the relationship between private and public life. The suburb was conceived as a safe haven from the noxious urban core—a place of serenity for family life to prosper. Federal programs financing the development of the suburbs had certain conditions; they supported racial covenants that excluded people of color from white communities and unequivocally denied mortgages to unmarried women. The primary beneficiaries of these new homes, designed for “a male worker and unpaid homemaker,” were the white middle class. Hayden writes that this socioeconomic dynamic is rooted in the “happy worker” movements of early industrial cities and would solidify into the status quo with the construction of suburbs, asserting that “men were to receive family wages and become home ‘owners’ responsible for regular mortgage payments, while their wives became home ‘managers’ taking care of spouse and children.” The power vested in male breadwinners would transform the home into a “container for female unpaid labor” and the stage on which the “fantasies of patriarchal authority” would play out, argues Hayden. But just as suburban sprawl was becoming a fixture of American life, women’s participation in the workforce was growing. The home as designed to fit the ideal family was quickly becoming outdated.

The rise of women’s employment would cause an imbalance in women’s relationship with domestic work. Hayden notes that the frantic housewife/wage earner would find herself torn between employment, commutes to and from the workplace, domestic chores, and the “physical and emotional maintenance” of the family. Traditional zoning practices exacerbated the strain on time and labor that intentionally isolated the residences from “shared community space—no commercial or communal day-care facilities, or laundry facilities, for example, are likely to be part of the dwelling’s spatial domain.”

To Hayden, this challenge to bridge domestic work with women’s economic position is not a private problem—it is a social problem that cannot “succumb to market solutions.” Responding to the rise of fast-food chains to replace home-cooked meals, commercial day cares, and television to replace childcare, and expanded credit on products for domestic work, Hayden warns that these market replacements lend themselves to creating exploitative conditions for workers. She writes that these jobs are often underpaid, nonunion, and unsecure, filled by marginalized women of lower-class status to substitute the unpaid domestic work of affluent families.

In Hayden’s Non-Sexist City, housing is a confluence of living, working, and supportive services designed around community-delegated, egalitarian support for domestic and public life. Hayden suggests organizing small participatory groups called Homemakers Organizations for a More Egalitarian Society (HOMES). HOMES strive to create an environment of shared unpaid domestic labor, supporting all residents in the paid workforce, eliminating segregation, eliminating programs that sex-stereotype work, reducing duplication of domestic labor, and supporting personal choice towards recreation and sociability.

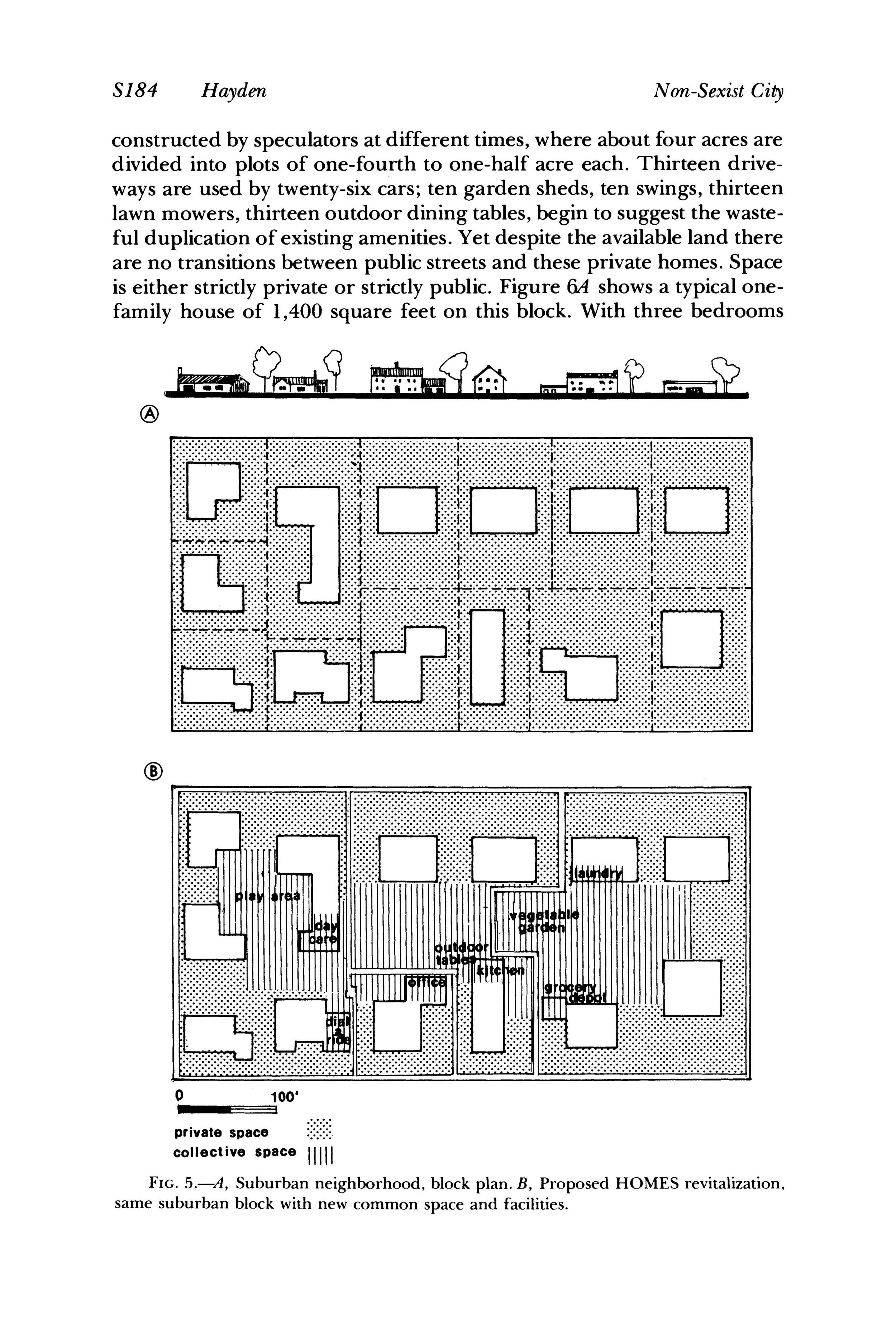

Hayden’s HOMES rely on grassroots organizing and collective bargaining to acquire zoning variances and legal conversions to accommodate the proposed structures. A HOMES group may consist of any number of households that establish housing with collective services, including day cares, laundromats, kitchens, grocery stores, a garage, gardens, and offices. Services are staffed by residents, compensated to eschew what Hayden calls “sex-stereotyped attitudes towards skills and hours.” Housing can be new or rehabilitated, taking a typical suburban block of homes and inverting the position of public and private space. Dwellings, side yards, and portions of front yards remain private, while auxiliary spaces are integrated into the community. Backyards are combined to create a shared park that the houses face instead of the street. Sheds and porches become community spaces. A dial-a-ride garage replaces numerous private cars, and appliances, such as washers, dryers, and power tools, are shared among neighbors. Alternatively, existing single family homes, designed with open plans, can be converted into duplexes and triplexes varying in size from studios to three bedrooms to create collective arrangements. Hayden suggests a limited equity housing cooperative—in which residents already share an economic stake—as a model for integrating collective services.

Hayden explores the ideas of a Non-Sexist City in several books following the essay’s publication. The Grand Domestic Revolution (1981) explores the material feminists and their stance on economic and spatial issues as part of women’s depressed social position in relation to domestic and public life. Redesigning the American Dream (1984, 2002) recounts the history of the American suburb, making clear the correlation between the separation of public and private life and strict divisions of gender roles.

Despite this advocacy, we continue to live in much the same housing that Hayden’s essay deems incongruous with an egalitarian society. We witness a housing crisis that struggles to provide secure and affordable housing—a crisis compounded by a legacy of segregationist policies—while communities struggle against city governments’ emphasis on the private market to resolve these issues. The Community Land Trust (CLT) model challenges that. It combines tenants, building owners, community organizations, and people living near the associated development to set aside land for housing that is independent of real estate market fluctuations. CLTs and the numerous organizations that support them demonstrate that housing equality continues to be an issue and emphasize that, like Hayden did in 1980, community control and participation are cornerstones to challenging discriminatory policies whose effects linger today.

References

"What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work"

Dolores Hayden, Signs, Vol. 5, No. 3, Supplement. Women and the American City (Spring, 1980), pp. S170-S187

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

1980

Hayden, Dolores. “What Would a Non-Sexist City Look Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design and Human Work.” Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, ed. Jane Rendell, ed. Barbara Penner, ed. Iain Borden, Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003, pp. 266–281.

1981

“Introduction.” The Grand Domestic Revolution a History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, by Dolores Hayden, MIT Press, 2000, pp. 2–29.

“Feminist Politics and Domestic Life.” The Grand Domestic Revolution a History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, by Dolores Hayden, MIT Press, 2000, pp. 291–305.

1984

Hayden, Dolores. Redesigning the American Dream: The Future of Housing, Work, and Family Life. 2nd ed., W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.

Tanaka, Aaron. “The Transformative Vision of Community Land Trusts.” Dissent Magazine, 20 Nov. 2015, www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/transformative-vision-community-land-trusts-boston-dsni.