In Architecture: The Story of Practice, architecture scholar, theorist, and activist Dana Cuff offers an in-depth analysis of the culture of architectural practice as a “social construction” by dissecting the untold contradictions between what it means to be and to become an architectural practitioner, offering suggestions on how to mend the gaps, and concluding that the design process is based on “collective action” and is fundamentally “a social process,” a result of negotiation.

Published in 1992 after ten years of research, the book draws on previous sociological and historical studies of professionalism and design practice. It owes much of its inspiration to Cuff’s colleague and mentor, sociologist Robert Gutman, whose book, Architectural Practice: A Critical View (1988) examined the challenges facing architects in a moment of change for the profession. Cuff inserts herself in this string of research while acknowledging a lack of literature at the time that described “the everyday architectural practice.” For six months, she employed sociology’s ethnographic method, paired with participant observation, to directly immerse herself in the life of three architecture firms, selected for their diverse range of office size and project types. Utilizing subsequent interviews of a total of seventy architects and developers, roundtable discussions, and informal interactions with practitioners, Cuff put together a comprehensive view of the history, development, and actuality of architectural practice by focusing especially on the divide between beliefs about the profession and the reality of practice. She identified this divide as the underlying origin of the ambiguity in defining the role of architects. The objective of her analysis and of her suggested areas for change is to create a better understanding of the architectural profession, which could “guide us toward making better environments” and “reinforce the profession’s role in unifying and standardizing its practices, an important source of professional strength.”

Cuff’s interest in this study stemmed from her own observations, as a student transitioning from university to working in the field of architecture, that the image of architects as portrayed in academia and popular culture as designing in isolation did not correspond to the actuality of the profession or “consider the range of activities, nor the people involved.” Throughout the book, she particularly focuses on opposing dualities and analyzes them in various contexts, such as understanding design issues (“Design Problems in Practice”), exposing them among the path from layperson to student to architect (“The Making of an Architect”), within the design-as-negotiation process (“The Architect’s Milieu”), and in the search for the meaning of excellence in architecture through the analysis of three variably complex projects as case studies (“Excellent Practice: The Origins of Good Building”). Within such dualities—the individual versus the collective, design and art versus business and management, decision-making versus sense-making, and specialists versus generalists—Cuff shows how architects tend to neglect one side over the other, thus perpetuating the ambiguity in their relationship with the profession, fostering the aura of mystery surrounding their work, and distancing them both from clients and the public. Cuff suggests acting within the field of professional organizations, the professional press, and in architectural education to shift the attention from the individual hand of the architect to the role of the profession in the design process as a collective sphere of action.

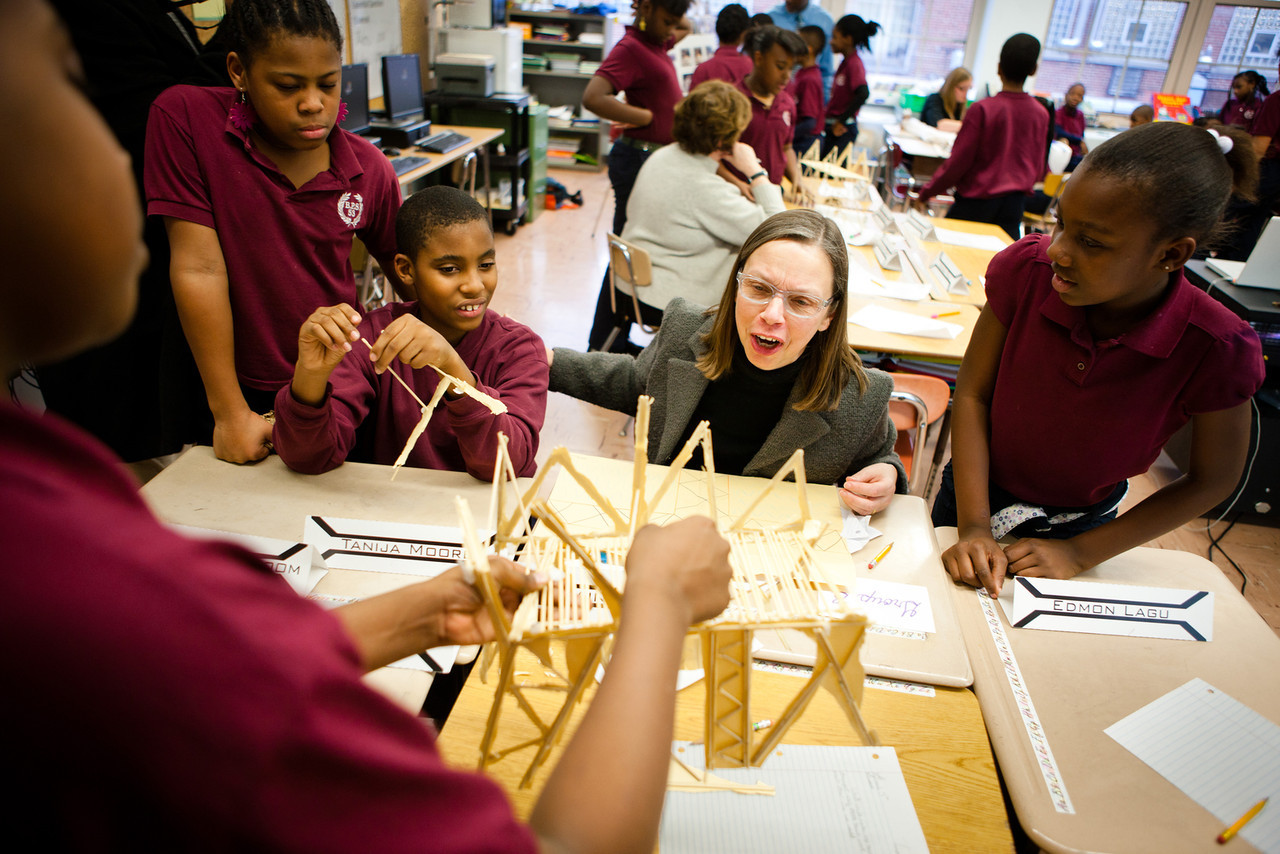

Cuff’s interest in “the scholarship around architecture that leads to . . . all sorts of agency” has been at the center of her academic career. Her observations on architecture’s role shifted from within the office environment to the outside urban context, focusing on where and how architects’ actions could be effective in the public realm. This culminated in the creation, in 2006, of CityLab, an experimental research and design center within the University of California, Los Angeles, which collaboratively links the university with the profession, the public, and city government.

Cuff wrote the book following a period when architects’ identities had been shaken by economic and political changes along with the crisis of the paradigms of the modernist movement. It was also a time in which the use of computer-aided design was still developing and the structure of practices and of the architectural profession was changing.

Today, at a moment when there are no defined architectural movements—when the idolization of “starchitects” seems to be waning in favor of more collaborative approaches to architecture practice and when BIM technology and the growth of design-build and integrated project delivery methods are reshaping the way architects interact with clients and consultants, the contradictions unveiled by Cuff still ring true. Furthermore, global tensions brought on by climate change, the increase of urbanization, and the outcome of the 2016 presidential election have inspired some American architects to move outside of their practices and into activism and advocacy. All the while the main institutional body of the architectural profession, the American Institute of Architects, is criticized by some for its inability to recognize that the profession is in crisis and to truly represent the interests of all registered architects. The Architecture Lobby and Who Builds Your Architecture? are two examples of organizations that advocate for guiding the debate toward issues that matter to all architects, particularly ones concerning fair working conditions for architects and construction site workers.

Even almost thirty years after the original publication of Cuff’s work, few studies have peered into the everyday life of architecture practice. Notably, researcher Albena Yaneva observed the daily activities of the Dutch firm OMA and recounted her findings in her publication, Made by the Office of Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design (2009). Though the conclusion Cuff draws—that architecture is a collective process, a result more of talk than of actual drawing—read today may sound obvious, books such as Architecture: The Story of Practice can inspire and remind architects to define their roles as professionals for the benefit of their own practices and of the society in which they continually seek to become active members.

References

American Institute of Architects. The Architect's Handbook of Professional Practice. 2014.

Cramer, Ned. "What Won't You Build?" Architect Magazine (April 2017)

Cuff, Dana “Athena Lecture,” Lecture at KTH Centre for the Future of Places, September 2017 (available on Vimeo)

Cuff, Dana “Act Like and Architect!” Lecture at Taubman College, October 2017 (available on Vimeo)

Cuff, Dana, and Roger Sherman. “Introduction.” In Fast-forward Urbanism: Rethinking Architecture's Engagement With the City. Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

Cuff, Dana. "Before and Beyond Outside in: An Introduction to Robert Gutman’s Writings." In Gutman, Robert, Dana Cuff, and Bryan Bell. Architecture from the outside in: Selected essays by Robert Gutman. Princeton Architectural Press, 2010, 13-27

Deamer, Peggy, Dunn, Keefer, and Shvartzberg Carrió, Manuel. “A Response to AIA Values.” The Avery Review. Issue 23 (April 2017)

Dovey, Kim. “Architecture: The Story of Practice by Dana Cuff; Behind the Postmodern Façade: Architectural Change in Late Twentieth-Century America by Magali Sarfatti Larson.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research. Vol. 13, no. 3 ( Autumn 1996): 261-264

Kaminer, Tahl. Architecture, Crisis and Resuscitation: The Reproduction of Post-Fordism in Late-Twentieth-Century Architecture. Routledge, 2011, 3-7

Larson, Magali Sarfatti. Behind the Postmodern Facade: Architectural Change in Late Twentieth-Century America. University of California Press, 1995.

Mayo, James M. "Architecture: The Story of Practice." Journal of Architectural Education. Vol. 46, no. 1 (September 1992): 61-62

McGuigan, Cathleen. "Common Ground in Unsettling Times." ARCHITECTURAL RECORD 204.12 (2016): 13-13.

McNeill, Donald. The Global Architect: Firms, Fame and Urban Form. Routledge, 2009.

Medina, Samuel. “Meet the Architecture Lobby Working to Change the Way the Professions is Structured.” Metropolis Magazine (December 2013)

Minkjan, Mark. “Is the Architectural Profession Still Relevant?” Failed Architecture (September 2013)

Roy, Ananya. “The Infrastructure of Assent: Professions in the Age of Trumpism.” The Avery Review. Issue 21 (January 2017)

Saenz, Michael. “Architecture: The Story of Practice.” American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 96, no. 6 (May 1992): 1780-1781

Saunders, William S., and Peter G. Rowe, eds. Reflections on Architectural Practices in the Nineties. Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Stevens, Garry. The Favored Circle: The social Foundations of Architectural Distinction. MIT Press, 2002.

Tijerino, Roger. "The Architecture Profession: Can It Be Strengthened?" Journal of Architectural and Planning Research (2009): 258-268.

Yaneva, Albena. Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design. 010 Publishers, 2009.