Sarah Gunawan & Julia Jamrozik

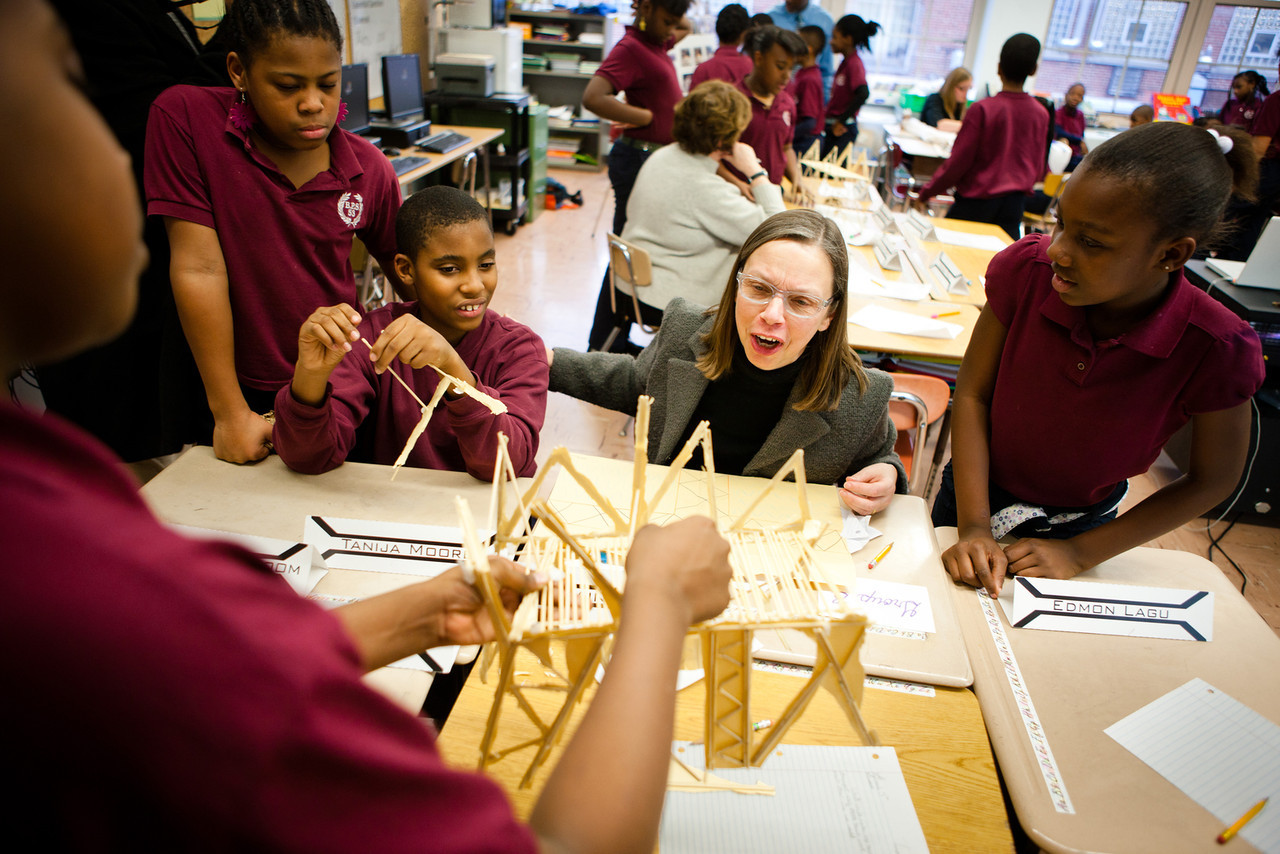

Architecture + Education Program, Buffalo Public School 53 Sponsored by the Buffalo Architecture Foundation, Architecture + Education Program, photography courtesy of Douglas Levere, 2011

The disability rights movement surfaced in the 1960s, building momentum through the collective effort of activists and protesters, and reached a pinnacle in 1990 with the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Universal Design emerged from the roots of the disability rights movement to advocate for environments that are accessible to the greatest extent possible to all people, regardless of age, size, or ability. Within Universal Design practice, the emphasis often remains on ability; however, this essay advocates that age, in particular youth and old age, offers a critical lens through which we can further expand inclusivity in design. Designing for youth and older adults requires us to consider a diverse range of physical, cognitive, and sensorial abilities. Through an examination of a cross section of theoretical positions and design projects, we argue that the design of playspaces for children and domestic environments for older adults are a form of applied activism, capable of empowering individuals of all ages.

Designing for Youth

Though implemented at the beginning of the last century with the best of intentions for the betterment and health of youth, playgrounds in the United States became standardized, formulaic, unsafe, and uninteresting by the 1950s. The 1960s finally saw a renewed interest in spaces of play through the collaborative efforts of parents, community organizers, and designers. Thinking of both the creative development of children and the urban potential of playspaces as community spaces, Paul M. Friedberg and Richard Dattner designed and executed a series of revolutionary spaces for play in 1960s New York. As both designers and writers,1 they were advocates2 for play as an essential activity in the lives of children and in the everyday spaces of the city.

As the historian and activist Susan G. Solomon documents,3 the decades that followed have again left US playgrounds in a sad state of uniformity. Yet major victories have been made in the last decade, from the group of parents who set up an adventure playground for kids’ self-directed play on Governor’s Island4 to the thoughtful design work by landscape architects such as Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, which integrates natural elements into urban playspaces.5 Those advocating for playgrounds that are inclusive to people regardless of ability or mobility, such as Harper’s Playground in Portland, are making still further strides.6

Philadelphia’s Public Workshop embodies yet another approach that creates opportunities for youth to learn design skills and apply them to create meaningful contributions to their neighborhoods through their Building Heros Project.7 This form of hands-on activism through education and making can also be associated with the Architecture + Education program run by the Buffalo Architecture Foundation and Beth Tauke at the University at Buffalo.8 As part of this initiative, architecture students and architects bring design into the public school classroom by introducing children to the profession and the playful and creative potential of design. This kind of focus on youth creates engagement—and ultimately empowerment and agency.

Designing for Older Adults

A demographic and cultural shift occurred in the mid-twentieth century that transformed the perception of aging within the United States—from a process of decline to an active phase of life known as the young-old.9 Age-specific suburban communities emerged across the southern states to accommodate this growing demographic.10 While these developments identified a critical need for environments designed to support aging bodies, they simultaneously segregated older adults from multi-generational communities. In the 1980s, Michael Hunt identified a new pattern of urbanization within older generations through the emergence of Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities (NORCs).11 The occupation of housing complexes by predominantly older adults marked a transition toward the concept of aging-in-place, in which older adults have the ability to live independently, comfortably, and safely within their own home and community.12

The aging of the American population over the decades since has motivated architects to advocate for spatial strategies that support aging-in-place across scales and building typologies. Höweler + Yoon has developed strategies for multi-generational living through their projects Bridge House and 10 Degree House. However, the construction of new age-considerate homes is not a viable option for many older Americans. The Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access (IDeA) at the University at Buffalo empowers individuals across New York State to maintain independence by designing and implementing home-environment modifications like expanded walkways, accessible bathrooms, and the installation of mobility aids.13 The University of Arkansas Urban Design Center (UACDC) has furthered this idea through a strategy of retrofitting existing suburban neighborhoods to enable a process of “aging-in-community”. Through the design of new spatial attachments to the single-family house their proposal encourages informal social interactions and entrepreneurial activity, which enables seniors to thrive within the fabric of the suburbs.14

The challenges older adults face extend beyond the process of aging to intersect with issues of accessibility, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. Several designers are grappling with these overlaps. Through attention to the heterogeneous experiences of older adults, these design advocates are responding to the intersectional needs of our aging population.

Age offers a critical and timely lens through which to advance inclusive design efforts within the architectural profession. Designers are once again embracing the creative and social potential of open-ended play and the benefits it has for children and communities at large. There is hope that advocacy at many levels may lead to more accessible and better-designed playspaces in more American neighborhoods. Simultaneously, with the American population of older adults projected to double by 2060,15 the practice has a responsibility to advocate for the diverse and intersectional embodiments of older adults through design. It is clear that better design for children and older adults can improve the quality and inclusivity of the built environment as an intergenerational space. By focusing on the specific needs of these two populations, designers have the responsibility and potential to act as advocates who can generate a sense of belonging and empowerment for individuals of all ages.

See: Friedberg, M P, and Ellen P. Berkeley. Play and Interplay: A Manifesto for New Design in Urban Recreational Environment. New York: Macmillan, 1970. And Dattner, Richard, 1948. Design for Play. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co, New York, 1969.

Hirsch, Alison B. "From “Open Space” to “public Space”: Activist Landscape Architects of the 1960s." Landscape Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, 2014, pp. 173-194.

Solomon, Susan G. American Playgrounds: Revitalizing Community Space. Hanover, Md: University Press of New England, 2005. And Solomon, Susan G. The Science of Play: How to Build Playgrounds That Enhance Children's Development. , 2014.

“play:groundNYC is a non-profit organization advocating for young people’s rights by providing playworker-run environments that encourage risk-taking, experimentation and freedom through self-directed play.” www.play-ground.nyc

With projects such as Teardrop Park, New York, NY (1999–2006)

www.harpersplayground.org and http://place.la/project/harpers-playground/

http://buffaloarchitecture.org/programs/architecture-education/

- Bernice Negarten, 1974 in “Age Groups in American Society and the Rise of the Young-Old

- Deane Simpson, Young-Old: Urban Utopias of an Aging Society

- "Staff Bios: Michael Hunt". University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Healthy Places Terminology”, October 15, 2009 https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/terminology.htm

- Center for Inclusive Design and Environmeental Access, “Home Modifications” http://idea.ap.buffalo.edu/Services/HomeMods/index.asp

- University of Arkansas Community Design Center, Houses for Aging Socially: Developing Third Place Ecologies, Arkansas: ORO Editions, 2017.

- Mark Mather and Linda A. Jacobsen, and Kelvin M. Pollard, “Aging in the United States,” Population Bulletin 70, no. 2 (2015).